“Today’s high (or low) temperature was an all-time record for this date.”

How many times have you heard that? This kind of news has been a staple of local weather forecasts for decades. And if you’d been keeping track, you would have noticed something curious. The number of days that produce sweltering record high temperatures has been eclipsing the number of days with frigid record lows.

That trend – a different way of measuring how the climate is warming -- has just been documented by researchers at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Boulder, Colo. and their colleagues. They found that from Jan. 1, 2000 through the end of last September, there were twice as many record highs reported as record lows: 291,237 highs vs. 142,420 lows.

The disparity is especially marked in the western half of the country, and it has been widening nationally for the last 30 years.

At Environmental Working Group, which is pushing for a strong climate bill to protect our food supply and natural resources, Mid-West Vice President Craig Cox said the new data confirms once again that Earth’s warming trend is already a day-to-day reality that requires urgent action. He noted that the devastating damage being done to Western forests by mountain pine beetles is partly due to warmer winters that help the insects to flourish and spread.

“Climate change is upon us – not something to worry about in the future,” said Cox. “It is happening now, with devastating consequences for our forests, causing damage that could well presage a host of problems down the road for agriculture, our food supply, and soil and water.”

The study’s lead author, NCAR’s Gerald Meehl, said in a statement that, “Climate change is making itself felt in terms of day-to-day weather in the United States. The ways these records are being broken show how our climate is already shifting.”

The new study’s findings emerged from millions of high and low temperature readings taken over six decades from about 1,800 weather stations across the country that have been operating since 1950 – a lot of data. Meehl worked with colleagues from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Climate Central and The Weather Channel to assemble and analyze the numbers.

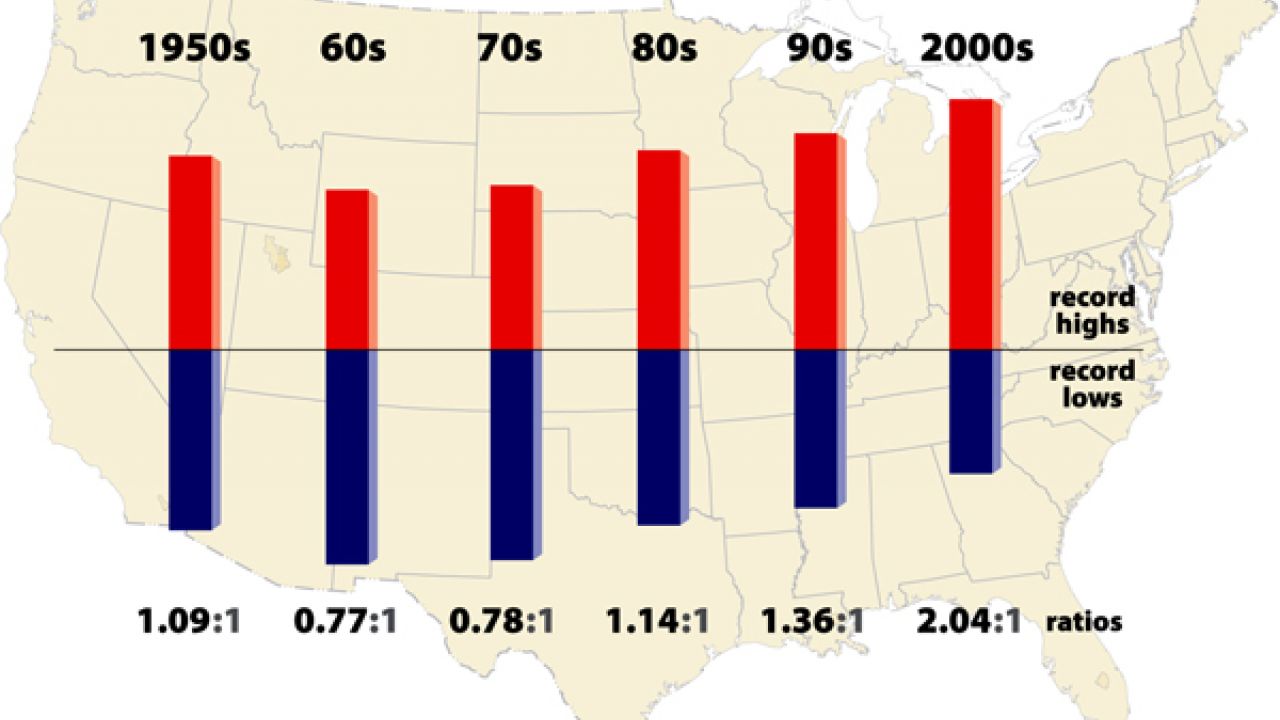

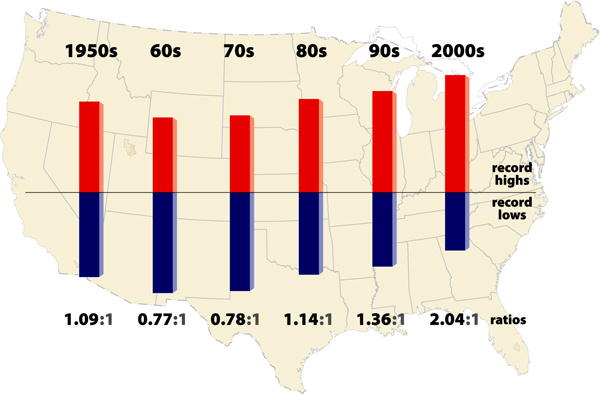

The data shows that in the 1950s the number of record high and low readings was almost even: 1.09 to 1. In the 60s and 70s there was a modest excess of record lows, but since the 80s the highs have been steadily pulling ahead.

This chart shows how the ratio of record highs to record lows has been changing:

(©: University Corporation for Atmospheric Research, graphic by Mike Shibao)

A sophisticated climate model used by the team predicts that if greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise, the high/low disparity will widen even further, to a ratio of about 20-to-1 by 2050 and 50-to-1 by 2100. Claudia Tebaldi, a statistician at Climate Central who is one of new study’s the co-authors, put it this way in a statement:

"If the climate weren't changing, you would expect the number of temperature records to diminish significantly over time. As you measure the high and low daily temperatures each year, it normally becomes more difficult to break a record after a number of years. But as the average temperatures continue to rise this century, we will keep setting more record highs."

The study illuminates another feature of the nation’s shifting climate. The rising ratio is driven more by a shrinking number of record lows than by a larger number of record highs. That shows that the rise in temperature is more dramatic at night, when temperatures aren’t dropping as much or as fast as in the past. This is exactly the shift that computer climate models had predicted.

Scientists understand pretty well why temperatures are warming more at night than in daytime.

As Meehl put it in a telephone interview:

“There are at least a couple of reasons -- chief of which is that the warmer air can hold more moisture, and moist air traps more heat so temperatures can't cool off as much at night as they used to.”

There are fewer periods of record cold, but don’t expect them to disappear altogether, Meehl said:

“Winter still comes. Even in a much warmer climate, we’re setting record low minimum temperatures on a few days each year. But the odds are shifting so there’s a much better chance of daily record highs instead of lows.”

The team’s paper is scheduled for publication in the peer-reviewed journal Geophysical Research Letters.