Over the past year, industrial produce growers and pesticide makers have made much ado about EWG’s Shopper’s Guide to Pesticides in Produce, which assembles federal testing data on many fruits and vegetables and makes it easy for consumers to see which have the most pesticide residues – and which have the least. The industry has ramped up efforts to attack the Guide, with the help, ironically, of a federal grant funded with your tax dollars.

The critics claim that the Guide’s “Dirty Dozen” list discourages people from eating adequate amounts of fresh produce, arguing that none of the levels of pesticide detected are deemed unsafe by the Environmental Protection Agency. Most consumers, of course, understand perfectly well that the Shoppers Guide is a just that – a handy guide. If they are concerned about pesticide residues, it provides a concise summary of the data, which, as the industry points out, is “long and somewhat cumbersome.” And EWG makes a point of encouraging everyone to eat more fruits and vegetables, not less.

What conventional growers and their pesticide industry allies don’t like to focus on is what’s been happening with long-term trends in pesticide residues. What the data shows is that overall, the percentage of samples on which pesticides are detected has been increasing – from 42 percent prior to the Shopper’s Guide to more than 70 percent in 2008.

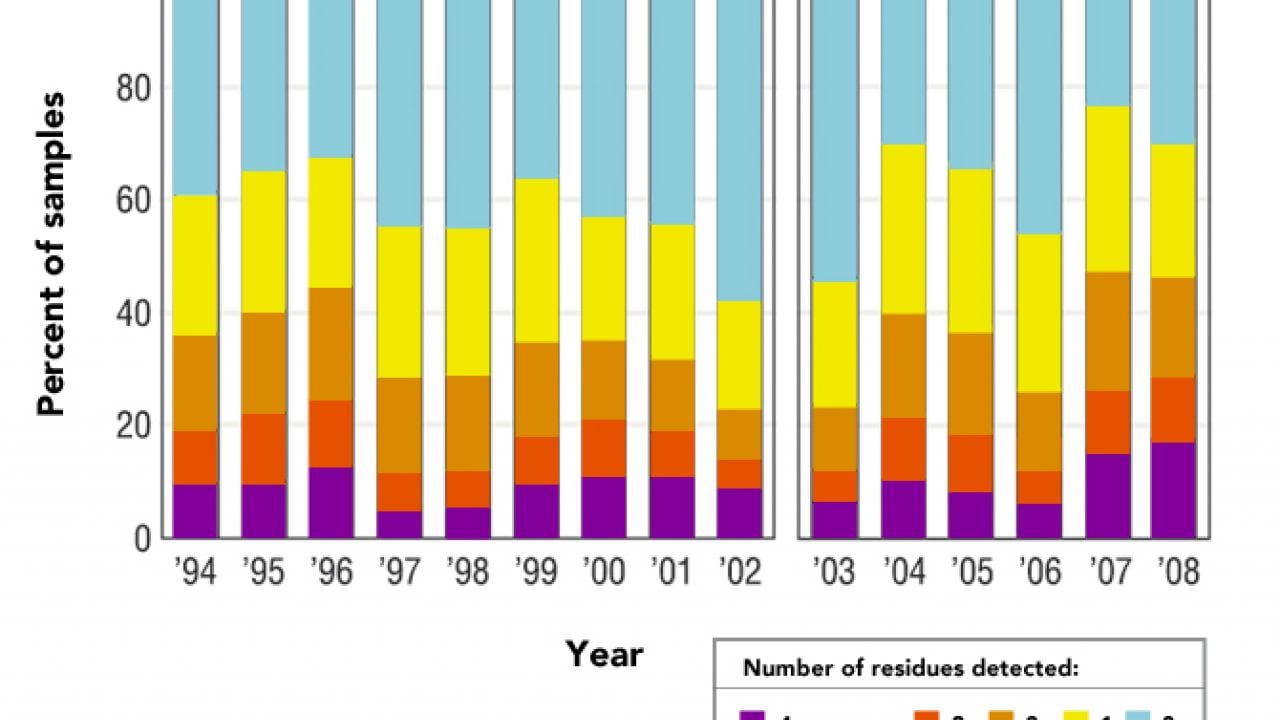

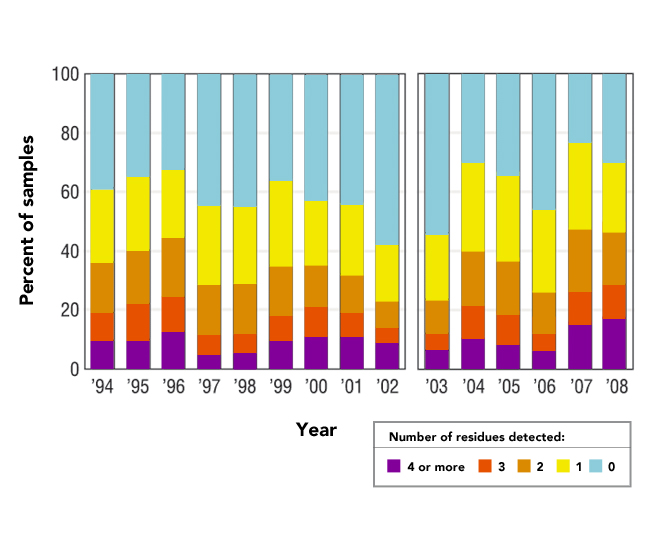

The chart below shows the overall rate of pesticide detections from 1994 to 2008. The red portion of the bar at the bottom reflects samples that carried 4 or more pesticide residues, and the grey portion at the top shows what percentage contained no residue.

Pesticide detections in US foods, 1994-2008

There’s a break in the chart between 2002 and 2003. That’s when the US Department of Agriculture changed its sampling procedures. Before 2003, if a pesticide decomposed into multiple chemicals that were themselves on the list to be monitored, each one was counted as a separate “exposure.” But in 2003, USDA began counting the original pesticide and its breakdown offspring as just a single exposure. In effect, it changed its counting method to make the numbers smaller – at a time when pesticide formulas were getting more complex.

Despite what was (arguably) a bit of accounting sleight-of-hand, the number of different residues found on fruits and vegetables continued to rise. In fact, from the time the Shopper’s Guide made its debut in 2003 to 2008, the number of samples carrying two or more residues doubled, and the number showing four or more almost tripled. In 2003, one of every three samples contained at least one pesticide residue, and one of every 12 contained several. By 2008, nearly eight of every 10 samples contained at least one, and one in six contained four or more. The trend is similar for samples with two or three residues. The only category that shrank was samples with only one residue.

During the life of the Shopper’s Guide, in other words, your odds of being exposed to pesticide residues on fruits and vegetables have almost doubled, and your odds of being exposed to multiple pesticides have more than doubled.

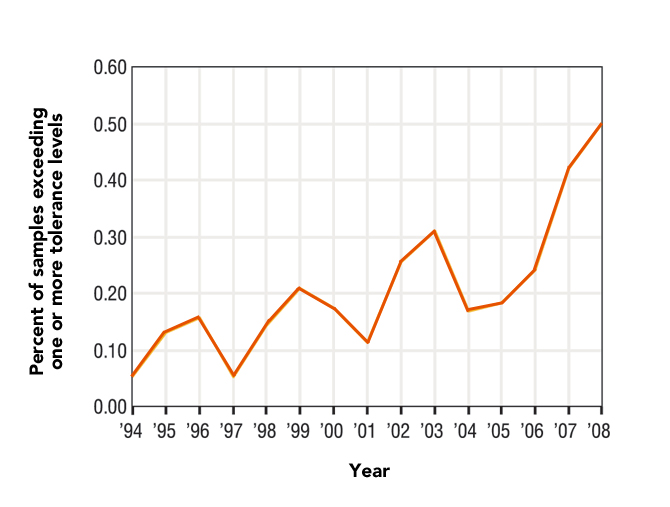

Not only that, but as the next graphic shows, from 1994 to 2008 the number of samples with residues exceeding the legal limits set by EPA went up tenfold. In other words, there is a ten times greater chance that the produce you eat today is carrying residue levels EPA deems risky. Again, this is despite the fact that fewer pesticide formulations are being monitored, and more produce is being grown organically.

Pesticide detections exceeding EPA’s allowable levels in US foods, 1994-2008

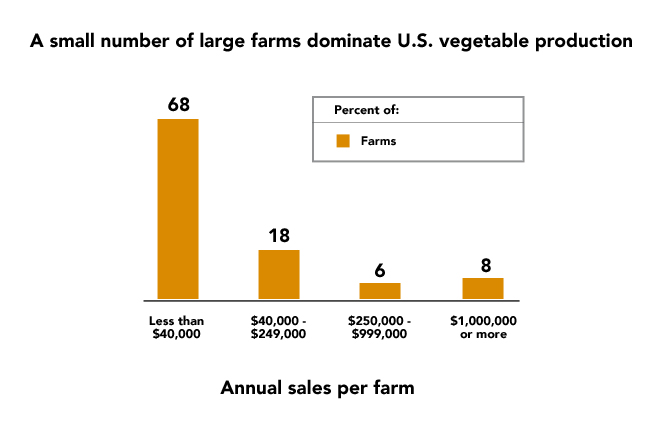

Why are growers applying more pesticides to fruit and vegetable crops? Farm consolidation is likely part of the reason. As this 2007 data from USDA’s Agricultural Resource Management Survey shows, more than 87 percent of the nation’s fruits and vegetables came from just 8 percent of the farms, which owned 79 percent of the cropland. By contrast, 68 percent of the farms, combined, own only 4 percent of the land and grow less than 1 percent of the crops.

The reason is that you simply can’t raise fruits and vegetables on mega-farms profitably without using pesticides to lower labor costs. Pesticides, while expensive, are cheaper than farm workers – even when they’re underpaid. Couple this with weak regulations that simply require pesticide users to “read the label,” a lack of compliance monitoring and generous liability protections for most uses, the need to ship produce great distances to consumers, and you have an environment where larding on more pesticide always makes economic sense.

Give the consumers some credit

The more you look at the data, the more you see the real problem with US fruit and vegetable consumption. Consumers are opting for produce that is chemical-free while industrial agriculture is applying increasingly complex chemicals to its crops and ever-increasing amounts of residues are going home on its fruits and vegetables. While EPA says those residues are “safe,” growing numbers of consumers are choosing to avoid them when they can.

That consumer mistrust is largely a product of pesticides’ history. Pesticide makers (and the government) use testing regimes aimed at ensuring that their products won’t kill people immediately, but they pay scant attention to potential long-term environmental and health effects. The policy is, basically, “wait to see what happens.” Inevitably, problems eventually do show up and then tend to attract substantial publicity. Testing new chemicals on your customers is not a strong marketing strategy, but it is one the industry has relied on for more than 60 years.

It was, after all, weak regulation of agricultural chemicals that led Rachel Carson to write Silent Spring, triggering the modern environmental movement more than 60 years ago. And new concerns keep cropping up. Pesticides are under scrutiny for their effects on monarch butterfly populations and bees. They have been linked to birth defects (repeatedly) and numerous adult health problems. And that’s just in the last few years.

When your product is designed to kill, your marketing is based on a “trust us” mentality, and your record of pursuing profits over consumer interests is so dismal that you scare your customers, business-as-usual is not likely to be a good strategy – no matter how many taxpayer dollars you throw at it.

People don’t refuse to eat vegetables because of the Shopper’s Guide. If they refuse at all, it’s because they don’t want to eat vegetables from people they don’t trust. Big Ag constantly defends mega-farm, chemical-intensive farming methods and downplays the never-ending river of studies that show the dangers of pesticide exposure. Growers and pesticide makers should spend their money to address the real problems, rather than spending taxpayer dollars on marketing campaigns that pretend those problems don’t exist and on attacking simple consumer information tools. They should rethink their testing programs and work with the EPA to develop a system people can have faith in. They should look at how pesticides are applied and push for monitoring systems that ensure accountability and result in produce that consumers actually want. They should look at their production models and change to farm more sustainably, with less chemical dependence.

Consumers’ interest is what makes the Shopper’s Guide so popular; the Shopper’s Guide doesn’t drive consumer interest. EWG’s message is so widely heard because it gives consumers what they want. Big Ag should try that.