A new study shows that implementing simple good stewardship practices for farmland – such as planting cover crops of grasses during the off-season and using fertilizer with greater care – could reduce the amount of agricultural pollution fouling the Gulf of Mexico by 30 percent.

And if farmers also restored wetlands to intercept and filter polluted runoff from their fields, among other practices, the amount of nutrient pollution reaching the Gulf would drop by 45 percent, the researchers calculated. The seven-member team published their results in the Journal of the American Water Resources Association.

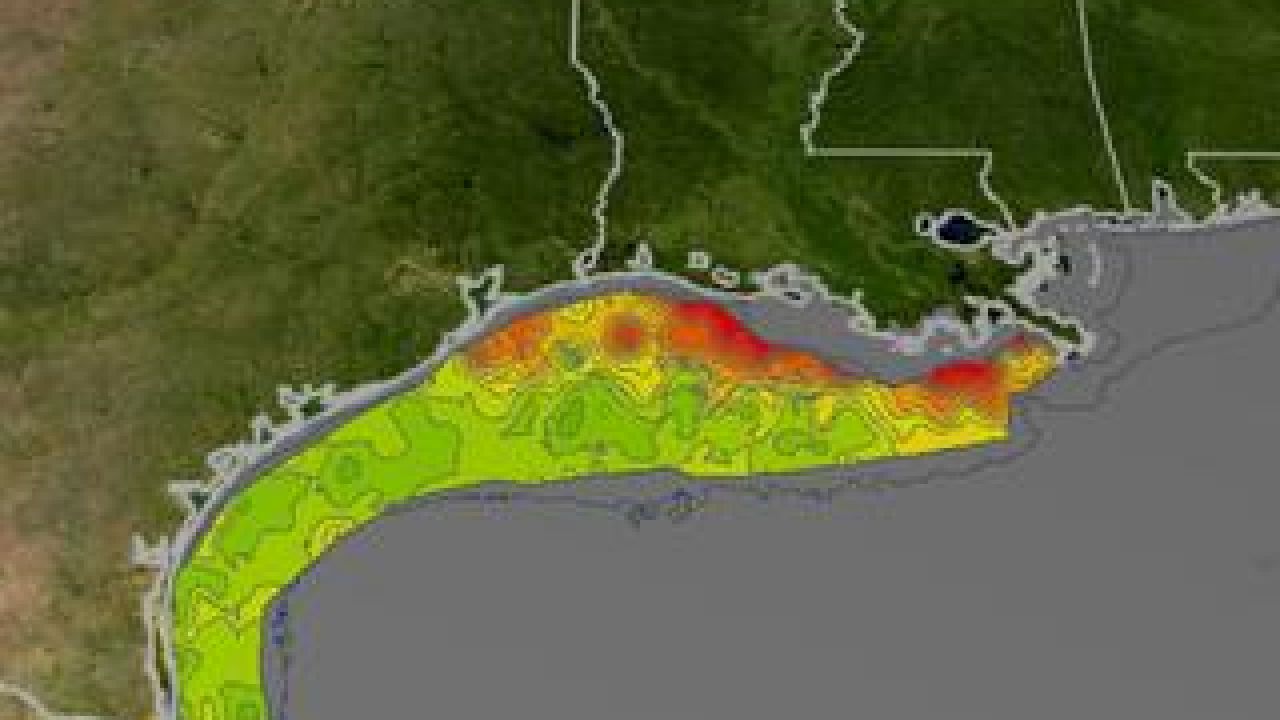

The nutrients in fertilizers ignite a biological chain reaction that depletes oxygen in the water. In the Gulf, that creates an annual “dead zone” the size of Connecticut where marine life cannot survive.

The new study’s results sound like good news, right?

Unfortunately, most of the growers whose fields ultimately drain into the Gulf can’t be bothered to plant cover crops or use fertilizer efficiently – even though the new study found that they could cut fertilizer use by 20 percent without reducing crop yields.

What’s more, Congress is once again poised to cut funding for programs that help growers take steps to reduce farm pollution.

And what about those wetlands that could be strategically restored to filter runoff? In the 2014 farm bill Congress actually cut funds for programs that support wetland preservation and, under pressure from farm groups, is currently pushing to change the very definition of wetlands to make it easier to drain the ones we have left.

The new study is a reminder that cleaning up Big Ag’s mess in the Gulf of Mexico, and Chesapeake Bay and the Great Lakes is not terribly complicated and would have minimal impact on farmers in the Mississippi Basin and beyond. As the authors noted:

A conservation scenario that combines nitrogen-management practices with a diverse suite of nitrogen-removal practices on 2.5 percent of the land in the Basin can achieve a 45 percent reduction in nitrogen while requiring the conversion of just over 750,000 hectares of cropland. Targeting efforts to those watersheds with the greatest cropland-use effectiveness can achieve the same goal with the conversion of just under 270,000 hectares of cropland, or 1 percent of the cropland in the Basin.

The study also serves as reminder that relying on voluntary action by farmers to minimize agricultural pollution is a dead end. Without a major new push by Congress, relying on voluntary conservation practices alone will continue to produce the same lackluster results – polluted water and rising costs – we’ve seen over the past 70 years.