We need a consistent approach to agricultural conservation.

Driving around central Iowa on a crop survey this spring, EWG analysts came across a far-too- common scene: adjacent fields reflecting disparate responses to the problem of agricultural runoff. (see photo below) EWG’s report on their findings, “Fooling Ourselves,” showed that voluntary programs to encourage planting of protective vegetation along vulnerable waterways were not achieving lasting results.

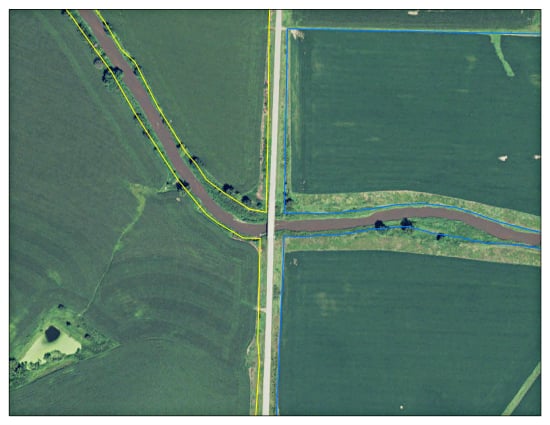

Figure 1 Caption: Adjacent fields show inconsistent responses to agricultural runoff. Stream boundary derived from digital elevation map. (National Agriculture Imagery Program, 2015. Iowa Department of Natural Resources, 2010)

These two Iowa fields tell the tale. Current voluntary conservation policies place a burden on farmers, taxpayers and waterways alike. Some growers participate, but others do not.

In the photo above, neighboring fields share a waterway called Brushy Creek, which is on the Environmental Protection Agency’s “List of Impaired Waters.” The two farmers treat the waterway differently.

The field on the right (outlined in blue) maintains a 50-foot buffer along both shorelines. The acreage in the buffer was enrolled in the federal Conservation Reserve Program – which is voluntary – in 2008. The field on the left (outlined in yellow) has virtually no protective grass buffers along the creek.

Figure 2 Caption: Roadside view of Brushy Creek bank on the left field (outlined in yellow in Figure 1) Photo shows no vegetative buffer and deteriorating stream bank. (EWG, 5-10-2016)

Figure 3 Caption: Roadside view of Brushy Creek bank on right field (outlined in blue in Figure 1) shows 50-foot vegetative buffer and healthy stream bank. (EWG, 5-10-2016)

Without protective vegetation or buffers between cropland and the creek, pollution from soil erosion, feeding operations, animal waste, pesticides and fertilizers can flow freely into the stream. Plowing right up to the crumbling stream bank allows some crop to fall right into the water, as seen farther upstream (see next photo).

Figure 4 Caption: Roadside view of Brushy Creek bank further upstream on the left field (outlined in yellow in Figure 1). Without a vegetative buffer, cropland is vulnerable to erosion caused by a meandering stream. (EWG, 5-10-2016)

The field on the left is classified as “highly erodible” – very vulnerable to soil erosion – by the Natural Resources Conservation Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. As a result, the farmer would have to follow an approved conservation plan in order to qualify for USDA benefits, although the federal government does not require riparian buffers. The field on the right is not classified as highly erodible.

So what have we learned?

The farmer working the left field is not in sync with his neighbor to the right. He’s doing his best to protect the waterway, but the payoff in cleaner water is limited because of his neighbor’s indifference.

The efforts of farmers who practice good land stewardship are undermined by those who don’t. And taxpayers, who have been supporting government subsidies to prevent soil erosion for three decades, aren’t getting what they pay for.

For conservation to be effective in improving water quality, it must be consistent. If we’re going to be serious about cleaning up America’s agricultural waterways, there needs to be a regionally enforced basic standard of care. Enacting a simple, universal 50-foot buffer requirement would give taxpayers and neighboring farmers a solid foundation for cleaning up our water.